We rush and worry. We pace and worry. We jog, and walk, and sit, and worry. We carry worry with us as a vestigial organ, and then we wonder why our chests feel tight, why it feels like we haven’t had a breath in days, why our blood pressure is high, and why the headaches never stop. And, all the while, we seek something to make the worry go away. Some of us seek it in pills and booze, food or excitement. Some of us see it in thrills and chills. And, some of us seek it by doing the most daring thing of all – leaping off the edge and diving wholeheartedly into the vast unknowns of our own inner worlds. There we find, like the philosophers and physicists have told us, the divine, whether we give it a name or not. To reach it, though, we must seek the depths and to do that we must also seek silence and the places which give it to us.

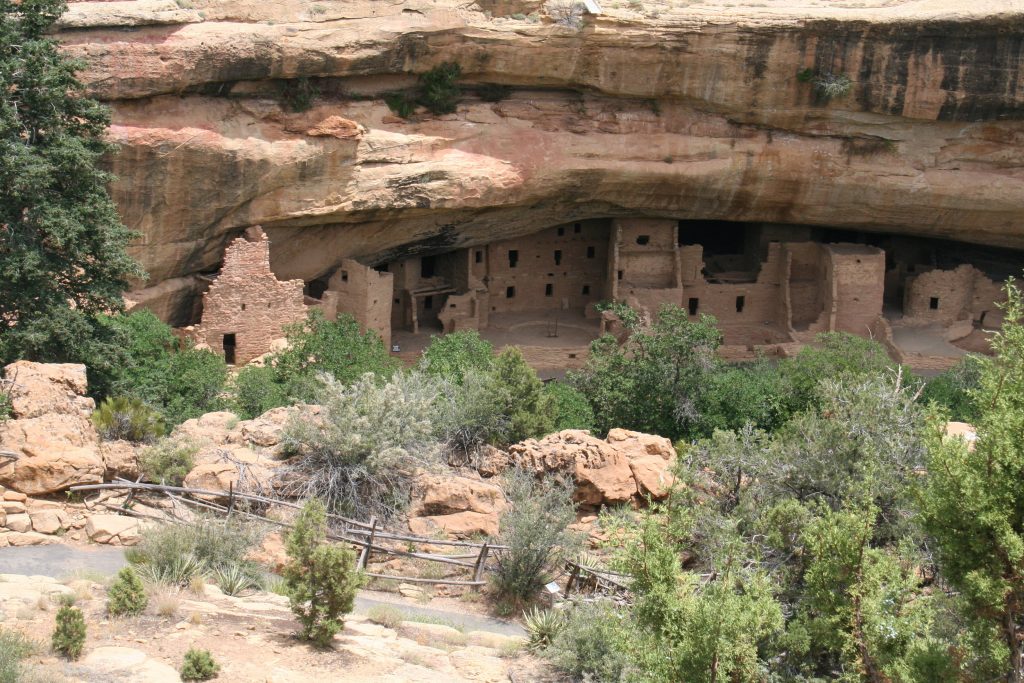

Mesa Verde, Colorado 2016 | Author’s photo

Sometimes those places are ancient. While there, we trace the footsteps of people who have gone before us. Our imaginations can help us see how our ancestors made the divine a part of the every day.

When in 1874 John Moss took the first photographs of the cliff dwellings, and in 1883, the prospector S.E. Osborn entered the Balcony House in what is now Mesa Verde National Park, no doubt they wondered what the preserved rooms originally contained. Later scientists, like Baron Gustaf E.A. Nordenskiold (credited as the first), have provided us with our understanding of what the rooms were used for. What we see when we look closely enough is that the holy space lived beside the hearth; it was intimate, part of family life, part of the every day.

The holy spaces and the hearth spaces, mixed. Mesa Verde, Colorado. Author’s own photo.

What were their beliefs? What were their customs? Does it matter? What matters is that they kept the divine near. It was dear to them, like the children they carried and the wives and husbands they chose.

And, when we walk into their homes hundreds of years later, along with the awe of how they built the structures and how they lived in them (how did they carry the water from so far away?), we walk away with an indefinable envy, not for their hardships, not for the gravity of their lives, but for their time, time to be silent and engage with the holy so intimately, so commonly, so matter-of-factly.

View of Cliff Palace, compliments of the National Park Service

from the Pipe Shrine House, Mesa Verde Colorado | compliments of the National Park Service

What can we learn from these teachers? We can learn that the divine doesn’t necessarily meet us only in the big campuses of our churches and synagogues and mosques. It doesn’t necessarily meet us in grand gestures or in dutiful motions. It meets us when we are quiet. It meets us when we open ourselves to the possibilities that live inside. It meets us when we find a place of sanctuary where we can walk in solitude so that we can walk in its company. It meets us in a place like Ebenezer Chapel will be: one where the possibilities are open and we have only to step inside.

JENNIFER BROWNING TEACHES ENGLISH, IS A PUBLISHED WRITER OF POEMS AND SHORT STORIES, LAVISHES KISSES ON BEAGLES REGARDLESS OF OWNER AND CAN BE FOUND MOST DAYS SURROUNDED BY FROGS.

JENNIFER BROWNING TEACHES ENGLISH, IS A PUBLISHED WRITER OF POEMS AND SHORT STORIES, LAVISHES KISSES ON BEAGLES REGARDLESS OF OWNER AND CAN BE FOUND MOST DAYS SURROUNDED BY FROGS.